Remastered 1960s Oscar-Nominee ‘A Time for Burning’ and 2018’s ‘Out of Omaha’ Screen at Aksarben Cinema This Week

This article was corrected on Feb. 4 to attribute a quote to ‘Out of omaha’ director Clay Tweel and add a comment from Producer Ryan Johnston

By Leo Adam Biga

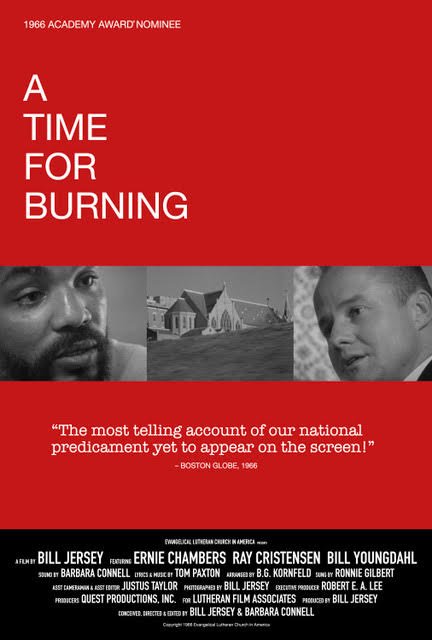

Depending on your point of view, Omaha has the infamy or distinction of twice being a microcosm on screen for systemic racism. Two documentaries made here more than half a century apart, the Academy Award-nominated A Time for Burning (1967) and the acclaimed Out of Omaha (2018), reveal hard truths about racial disparity still rarely seen in American cinema. Now, for the first time publicly, the films are being screened as a double feature in the city that birthed them.

Aksarben Cinema is presenting the hour-long Burning with its cinematic twin, the 90-minute Out of Omaha, February 4-10.

In 2020 Burning underwent a remastering process courtesy of the Film Archive of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Due to COVID-19, the remastered version is just now reaching theaters. The film’s ground zero, Omaha, is getting the first preview screening. A fall premiere is planned for the Academy Museum in Los Angeles.

A major distributor has expressed interest in picking up Burning, which may play festivals and screen on PBS. Interest extends to possible dramatic narrative film and theatrical adaptations.

Produced by Lutheran Film Associates (LFA) in a then-partnership between the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod (LCMS) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), the film is now solely owned by ELCA.

Available prints the past few decades showed signs of deterioration in a grainy image and tinny sound. Director Bill Jersey is grateful his best-known work is getting new life in a quality, just-like-new print.

Rarely have a pair of films spoken so eloquently or transparently about the oppression and division of a city and how it mirrors the polarization of a nation. Decades before Black Lives Matter and Critical Race Theory, Burning made many white people uncomfortable with its from-the-gut condemnations and moral equivalencies. It still does. Hurt feelings over it persist at Augustana all these decades later.

Burning was made by Bill Jersey and Barbara Connell as an LFA commissioned project to ostensibly show the church’s support of civil rights. When Jersey heard about a progressive, newly installed young pastor, Bill Youngdahl, at Augustana Lutheran Church in Omaha, he followed his storytelling instincts here. The idealistic, naive Youngdahl preached a doctrine of inclusion to a conservative white congregation stuck in their ways. The inner city parish did no outreach with the Black neighborhood within walking distance of its doors. When Youngdahl pushed fellowship with members of nearby Black churches Calvin Memorial and Hope Lutheran a controversy erupted inside his church that led to his ouster and a deep split in its ranks.

“We did a film about individuals in a church structure struggling with the issue of race in a way that I think represented how America was dealing with race at the time,” Jersey said. “Not the crazies in the South who were using fire hoses and attack dogs. Not the urbanites who were frustrated for many other reasons and setting fires to the banks. But average people being who they are authentically.”

“There’s a universal important lesson in the film — that change is hard. That change can be costly, but that resistance to change is a killer. It makes even the simplest efforts impossible.”

For the film’s 40th anniversary DVD release, Jersey noted, “There’s a universal important lesson in the film — that change is hard. That change can be costly, but that resistance to change is a killer. It makes even the simplest efforts impossible.”

His insistent, intimate, cinema verite camera captured the internal conflict among church elders. In barber Ernie Chambers, he found a community activist with a poet’s soul to articulate the historical-social context around the systemic racism laid bare on screen.

“Nobody in that film appears because a filmmaker dragged them in,” said Jersey. “Everyone appears because they were in some way directly involved with what was going on in that community. I feel that is, in fact, its strength — it’s a story of individuals who faced one another and confronted one another. No one was ever set up to expose their prejudice.”

When segments of the still work-in-progress film were seen by Lutheran officials, there was outrage over its portrayal of a church in crisis, unwilling to embrace racial reform. Nebraska Lutheran leaders filed a protest with the national executive council, branding the film “a disgrace to the church.”

“No, this is the story, it’s an honest film — keep making it,’ even though this isn’t what the church wanted to say about itself.”

Jersey said he gave LFA officials the option to “cancel the project and take the footage,” making clear “I wasn’t going to change a thing.” He recalled, “To their everlasting credit, they said, ‘No, this is the story, it’s an honest film — keep making it,’ even though this isn’t what the church wanted to say about itself.”

The film’s executive producer, the late Bob Lee, said officials “felt it was more important to see the church wrestling with the problem than to have a pat solution,” adding, “The consensus was the film was a good way to deal with this problem because it generated all kinds of discussion and still does.”

By comparison, Out of Omaha sparked no controversy.** That’s because the unjust judicial and law enforcement systems it exposes are open game in this woke period. It follows brothers Darcell and Darrell Trotter as they navigate systemic mass incarceration traps that threaten to make them statistics. Unlike Burning, which features the lighting rod antagonist Chambers, Out of Omaha focuses on the sweet-natured Darcell’s attempts to live in peace.

Ernie, the Prophet

Though Chambers was not yet a state legislator, he used Goodwin’s Spencer Street Barbershop as the base for his community advocacy and critiques. He’s the conscience of Burning’s intense interrogation of Christianity’s hypocritical practices and society’s racially biased stances.

The consternation the film aroused meant the era’s three commercial television networks “wouldn’t touch it,” said Chambers, who feels its unflinching indictment of mainstream values was too strong a medicine for timid white executives and advertisers.

The film did find a platform on PBS, which led to the doc’s themes becoming the subject of commentaries in national media and community forums across the country. Reaction to Burning prompted CBS to produce a news special, A Time for Building, on the fallout from the Augustana fissure. New leadership at the church encouraged self-reflection and education. Neighborhood outreach programs began. Some still question its commitment to racial reckoning, however.

Though Burning’s time capsule portrait of where America was with race in the 1960s has kept it in circulation all these years in select schools, churches and community organizations, there are those who feel it’s not gotten the wider viewership it deserves due to its still provocative content.

Artifact and Echo

For Out of Omaha producer Ryan Johnston, an Omaha native, and director Clay Tweel, Burning is not only a valuable artifact but a stirring echo of their own film.

“I have been a huge fan of A Time for Burning since I first saw it. Omaha has a dark history when it comes to race and oppression. Our film shows how much of that history still resonates and impacts lives in Omaha today,” said Johnston. “There’s a cool synergy here because I don't think Out of Omaha exists without A Time for Burning,” added Tweel. “Our story really takes place in the here and now. In a lot of ways it’s a very personal story of a few people from North Omaha. But it also references much larger trends and ideas about our society and culture related to inequality, oppression and systemic racism.”

Tweel thought enough of Burning to use excerpts from it in his own film. A memorable scene in Burning sampled in Out of Omaha depicts Chambers lecturing Youngdahl while cutting a child’s hair about the sins of the church and society. He correctly anticipates that if Youngdahl continues trying to forge racial integration, his church will turn against him. Chambers’ extemporaneous deconstruction of racism plays like the soliloquy of a seer.

Jersey echoes others in saying Chambers serves as “the prophet” figure of the story who foretells “the American tragedy” that unfolds.

In another scene, shop owner and fellow activist Dan Goodwin Sr, is seen cutting the hair of his then-6-year old son, Dan Jr. while listening admiringly to his friend speak truth to power. When the film found a national audience, Goodwin accompanied Chambers on a nationwide speaking tour in conjunction with screenings and town halls.

A Cinema Synthesis on Race

The shared relevance of the two films’ themes creates a cinema dialogue about race. Tweel leaned into Burning for background, saying it “had a huge influence on me when making Out of Omaha.” He added that Burning “gave me insight into how the civil rights movement played out in the Heartland and how Omaha was similarly affected to those cities and towns with more notable unrest.”

Pairing these films provides a synthesis of Omaha’s racist past and present unlike anything else except perhaps the Undesign the Red Line exhibition at the Union for Contemporary Art.

“I continue to be struck by how uniquely divided Omaha remains, particularly in terms of Black racial inequity. When you watch these two films in succession, it feels impossible to deny that reality. ”

“It’s a real honor for me as a producer to see our modern social justice-themed film associated with this civil rights era masterpiece,” said Johnston. “I continue to be struck by how uniquely divided Omaha remains, particularly in terms of Black racial inequity. When you watch these two films in succession, it feels impossible to deny that reality. I think that’s an important thing to communicate.”

Tweel said he “purposely ended” his film with clips from Burning “to make the audience position this personal story they just witnessed into the larger historical context in which it is playing out.” Tweel added, “Darcell’s story is unique, but also universal, as he lives out in real time the struggles Ernie Chambers articulated 50 years earlier. I wanted the audience to reckon with the extent to which our society has yet to make meaningful change.”

Burning helped make Chambers a national figure in the mold of fellow Omaha native Malcolm X, who was assassinated in early 1965, the same year the doc was shot. Chambers and Malcolm X met only one time during the previous year when the former Black Muslim leader spoke in his hometown, and the two social justice advocates and intellectuals convened.

For its 40th anniversary, Chambers joined Jersey for special events commemorating it. Talkbacks followed Film Streams screenings in Omaha. COVID concerns are preventing that this time around.

Sadly, everyone associated with the film’s rediscovery agrees nothing’s changed to make either Burning or its companion piece, Out of Omaha, any less true or pressing.

Aksarben Cinema is located at 2110 South 67th Street. For show times visit the website or call 402-502-1914.

Link to Leo Adam Biga’s 2007 two-part story on A Time for Burning in The Reader and 2020 two-part story on Out of Omaha for NOISE.