Omaha Has a Strong Mayor, Weak Council System of Government. Why? Can it Be Changed?

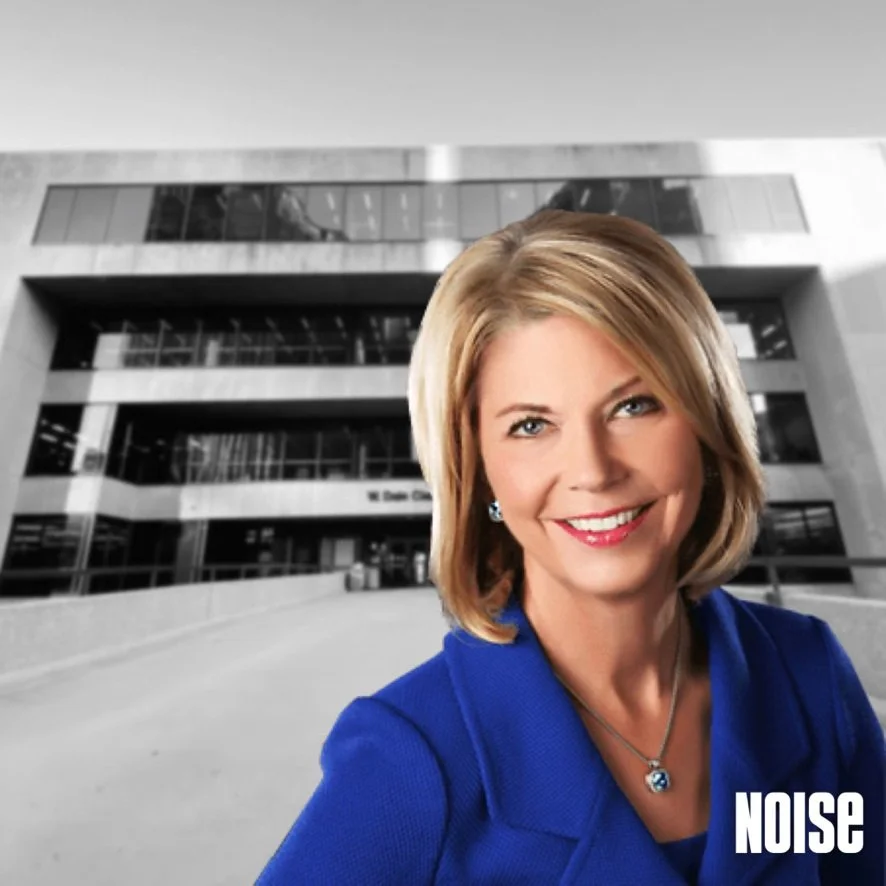

Image credit: Myles A. Davis NOISE

By Pete Fey

Pete Fey is a former employee at the W. Dale Clark Library. He lives in Omaha and will graduate in May from the University of Missouri with a Masters of Library and Information Science.

It is hard to miss the exasperation in Omaha City Councilman Vinny Palermo's voice at the February 1st, 2022 council meeting, where the body, by 4 - 3 vote, approved lease agreements for new public library facilities. For -- as readers following the story in NOISE are no doubt aware -- these were no mere lease agreements; in effect, their approval cleared the way for the demolition of the W. Dale Clark library, to be replaced by a forty-story office building that will radically alter the character of west downtown.

Start video at 1:26

And yet, as Palermo holds court for twenty-five minutes, grilling Mayor Stothert's deputy chief of staff over lack of transparency, lamenting how Omaha is "better than that," it is clear the councilman's frustrations have little to do with the actual lease agreements, and more with how the lease agreements came about. Plans for the downtown library and the library system were so secretive, Palermo explains, that to learn more about the plan he had to attend a public forum at his local library. "It is hard for people to believe that," he says, "that someone on the city council doesn't know what's going on. It's the truth."

“It is hard for people to believe that— that someone on the city council doesn’t know what’s going on. It’s the truth.”

Taken in full, then, Palermo's comments can be viewed as a live demonstration of a man reckoning with the limits of his position. This is not to say that he doesn't have a point; he was not the only city council member to voice their disproval about lack of transparency from the mayor's office, and the Omaha World-Herald even penned an editorial calling for future library plans to be built on "community dialogue and trust-building." Nevertheless, while Omaha may or may not be "better" than the opaque business dealings that put the W. Dale Clark library on the chopping block, the reality remains that under Omaha's strong mayor system of government, there is no legal imperative for Palermo and his fellow council members to know any more about the library lease agreements than they did. Under a strong mayor system, the mayor is...well, just that. Strong.

THE STRONG MAYOR SYSTEM

Although I had heard the term bandied about, and understood to some degree that the executive branch in Omaha has considerably more power than the legislative, I did not truly understand the purpose and nature of the strong mayor system until I read Harl A. Dahlstrom's 1987 biography of Omaha's 42nd Mayor, A.V. Sorensen and the New Omaha. Sorensen, while best known today as the namesake of Dundee's public library branch, as well as a particularly confusing northwest Omaha parkway, was a businessman who came to local prominence after he was named president of the Omaha Chamber of Commerce in 1955. The following year he would run as a delegate for the Omaha City Charter Convention.

That convention -- which Sorensen would serve as chairman of -- would bring about a marked change in Omaha's system of government, transforming it from a commission system to the strong mayor system we have today. As Dahlstrom explains, the commission system, introduced in 1912, "combined executive and legislative functions...Once elected, the seven councilmen, also known as commissioners, divided seven administration departments amongst themselves. One of the seven commissioners was chosen by his colleagues to serve as mayor."

Eventually, however, the commission system began to be viewed by a segment of Omaha's business community as too inefficient to rise to the challenges they perceived as facing the city in the postwar years. The city couldn't afford to be bogged down by the bureaucracy and indecisiveness which, in their view, characterized the commission system. The city needed to be run by someone with a vision, and the power to see through that vision. The city needed to be run more like...a business.

The convention, then, which according to Dahlstrom had "a decidedly upper-middle class quality," made up almost entirely of white men, went about creating the conditions for Omaha to be run like a business. In the new system they ended up with, the mayor— elected separately from the city council— would now have considerable authority over the day-to-day operations of city government, much like a C.E.O. The city council, which under the old system held most of the power, would be reduced to something akin to a company board of directors. No longer, for instance, would city departments be run by elected commissioners, but instead by cabinet members appointed by the mayor, people who did not even need to be approved by the council.

CHARTER REVIEW CONVENTION

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the city charter convention of 1956 is that, when it began, the expectation was not necessarily that an entirely new government would be formed. Indeed, in an ironic twist of fate, as the convention would end up stripping them of most of their power, it was the city commission itself, wanting to make amendments to the current commission system, that placed an item on the August 1954 city election ballot asking voters to certify the creation of a charter convention. This issue would pass, clearly, as would the eventual renovated, strong-mayor city charter itself, meaning that, for all its faults, our current strong mayor system does at least have the veneer of democracy. It was not forced on us, per se.

But the strong mayor system is not working. Dahlstrom describes the goal of the 1956 charter convention as creating a "rational, businesslike, and efficient operation.” Problem is, Omaha is not a business. It may be businesslike for the mayor and her staff to make backroom deals with a Fortune 500 company so they can bulldoze a library and build a corporate headquarters, but it is not in the public interest. It may be businesslike to have a city entrenched in car culture, whatever the human cost, and to the detriment of equitable, free public transit, but it is not in the public interest. It may be businesslike to hand over control of Omaha's baseball stadium and convention center to MECA (Metropolitan Entertainment and Convention Authority), a group of unelected officials almost entirely made up of wealthy, well-connected people, but it is not in the public interest.

It may be our current system but it doesn’t have to be. So how can it change?

One small step may be able to take place next year, during the 2023 City Charter Review. Unbeknownst to many Omahans, the city charter calls for, "at intervals of not more than ten years...a Charter Study Convention to be appointed by the Mayor with the concurrence of the [City] Council." This review convention can suggest recommendations to the council, which can then make moves toward adding them to the city charter. Traditionally the convention has had twenty-five members, some of which have been recommended by the mayor, others by city councilmembers (each of the seven council districts must have at least two representatives).

Now, of course, it seems unlikely that a convention made up of people appointed by the mayor would then be able to turn around and limit that mayor's power, or, for that matter, create a new type of government. Yet in looking back at the charter review convention's past renditions, it is obvious that the convention presents an opportunity to discuss demonstrable changes to our city. The 1993 convention, for instance, discussed the possibility of merging the Douglas County and Omaha city governments, a change that, while complicated and of uncertain value, would almost assuredly require the city charter to be rewritten. The 2003 convention discussed the possibility of making it a requirement that employees of the city government actually reside in the city, something that would disqualify the current chief of police, Todd Schmaderer, who lives outside of the city limits.

To be sure, it is also not out of the question that Mayor Stothert will, similar to how she has stacked the Omaha Public Library Board of Trustees, stack the 2023 convention with her allies in order to use it to increase her power. Nevertheless, it seems important that Omahans who want to see a change in our government, to make it truly our government— not just that of an autocratic mayor and her business friends— should try to get seated at the convention. A.V. Sorensen used his post as convention chairman in 1956 to get elected to the city council, and then the mayor's office. Other convention members have used the position as a springboard to more powerful positions. The 2013 convention, for instance, featured Brinker Harding, who was subsequently nominated to the Omaha planning board before being elected to the city council. Also participating in the convention that year was Symone Sanders, who soon became a fixture in national Democratic politics, serving on Bernie Sanders' 2016 and Joe Biden's 2020 presidential campaigns before becoming a chief advisor to Vice President Kamala Harris.

Pete Fey

More important than the actual results of the 2023 review convention might actually be the ancillary benefit of having people who want to see a more just Omaha getting a chance to see an up-close example of how exactly our city is run. It might, indeed, be an opportunity to answer what could be the most important question facing not only Omaha, but the whole country: is change possible within our current system? Can systemic change occur in a system so irrevocably broken, so irrevocably broken on purpose?