The Black Church in Omaha

A Series By Leo Adam Biga

St. John African American Episcopal Church at 22nd and Willis in North Omaha. Photo credit: Kietryn Zychal NOISE

Installment IV

St. John AME

Nebraska’s Oldest Black Church Keeps on Keeping On in North Omaha

By Leo Adam Biga

It was 1865. The American Civil War was finally over. Nebraska— still a territory— was two years from statehood. In the frontier town of Omaha, the first Black house of worship in Nebraska Territory was founded in a private home near downtown. Starting with merely five worshippers, St. John AME (African Methodist Episcopal) Church grew and moved north as Omaha matured from a frontier outfitting hub into a river, railroad, stockyards and meatpacking metropolis.

Once St. Johns moved to North O, members built a succession of three church buildings (one designed by Black architect Clarence Wigingtom) before settling into the current Prairie School-inspired structure at 2402 North 22nd Street. Blacks migrating from the Deep South helped swell its ranks. St. John’s third building at 25th and Grant eventually became St. Benedict the Moor, the city’s historic Black Catholic church. By the time architect Frederick Stott’s striking Prairie design of the new St. John’s worship center was dedicated in 1943, the mega church-sized congregation exceeded 1,000 members. In recognition of its bold visual statement – the Prairie style was an unusual choice for an urban church of that period – the building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and designated an Omaha landmark.

Overflow attendance at Sunday services was common and the pews were filled with both working class and white-collar members. St. Johns community outreach extended everywhere. “We were the Salem of that day,” third-generation member Louise Latimer II said, referring to Omaha’s modern mega Black church, Salem Baptist. The semi-retired social worker and community organizer was a congressional caseworker for Nebraska elected officials, making her one in a long line of St. John members to serve in the political arena.

Today, membership’s down to 65. Normal Sunday services draw a fraction of that, leaving most of the large sanctuary empty. Even so, the church’s good works continue. Though St. John’s may not carry the cachet it did when churches like it ruled the Black community, its enduring heritage survives in legacy families whose membership extends over generations, living reminders that African Americans have long been on the Great Plains.

The sanctuary at St. John AME. Photo courtesy of Northomahahistory.com

St. John Legacy Families

Matriarch Phyllis Brown is a descendant of the Speese homesteading family that founded the Black settlement of Dewitty in north-central Nebraska’s Sand Hills. Her grandparents attended St. James AME there. The family resettled in Omaha, joining St. John’s, where they’ve remained fixtures ever since. Membership extends over six generations to her daughter Deann Brown, grand-daughter Sabrina and great-granddaughter Savannah.

Another legacy family, the Mosleys, goes back five generations. Shaunielle Mosley, her mother Gail, her brother Shannon and her son Braylan all belong. Her ancestors, the Roberts, migrated to Omaha from Texas, becoming the first in her family to join.

“It’s an honor. The fact it’s been around that long is kind of amazing. We’ve known so many different families connected with the church. We’re still there. It’s still going strong. We really take pride in being members. We can’t imagine being any place else,” said Shaunielle, a U.S. Army veteran now with the Federal Aviation Administration.

“It’s been around for over 150 years and I think it’s really cool we’ve been able to be a part of that for so long,” said Braylan, an Omaha North High School junior planning to attend a historically Black AME college or university.

The Young People’s Division (YPD) participates in the Sunday church service. Savannah Brown-Harris, Ahmirra Brown-Hayes, Adonis Forte, Kyle Hutcherson, Braylan Mosley and Don Hannon. Photo credit: St. John AME

Braylan, president of the Young People’s Division (YPD), was 5th District Youth of the Year in 2021. “It felt very special because the 5th District is from California all the way to Missouri and they could have chosen anybody, but they chose me. I feel very blessed.”

Most of his classmates don’t attend church, but he feels he’s where he needs to be. “I’m thankful for everything the church has done for me and taught me.”

Deann Brown said legacy families like hers and the Mosleys personify the church. “One thing I can say – we are dedicated people.”

Latimer’s mother and maternal grandparents were St. John’s members. When her mother married, her parents moved to St. Paul, Minn., where Louise was born. The family moved back to Omaha when she was a child, St. John’s became her home church until, like Goodlow, she left as a young adult. “But there was just something saying ‘You need to go back’,” she recalled. A former teacher of hers who was active in the church gave her such a warm welcome upon visiting, she said, “I never forget that experience. It was a booming time then. Pastor Calvin McMillan got me involved as a trustee. When I first came back– to now– this church has always been an anchor for me and my life.”

She brought others back into the fold with her. “I actually started my family back. My mother got involved in the Women’s Missionary Society and served as missionary president for many years. Now I’m the president, so I took that (family legacy) and kept it going.”

Just as a preacher heeds a calling to serve, she said, “When you are active doing things in your church it’s your ministry.” Coming of age as a woman of faith, she said, “I looked up to a lot of individuals as role models,” adding, “They took me under their wing, they guided me through a lot of things.”

A vital function of a close-knit church like St. John’s, Latimer said, is giving collective support to young people like Braylan through everything from axioms to scholarships.

“We care how our young people do in school, what kind of grades they get. They not only have their parents to answer to, they have their church family. You’ve got parents pushing, church family pushing, the pastor patting you on the back, saying, ‘You did a good job.’ That gives that preparation. We’re getting them ready ” said Latimer, “and our kids are excelling.”

This it-takes-a-village training ground provides accountability, motivation, and encouragement. “That comes from a long line. We all have had that,” said Latimer.

A choir, instrumentalists and the minister outside of St. John AME Church at N. 22nd and Willis in 1939. Photo courtesy of Northomahahistory.com

Past and present are never far apart at St. John’s, whose elders preside over a church where succeeding generations experience Christian formation and service. When Latimer was a girl, her mother impressed upon her the need to speak up, calibrate her words and look people in the eye when addressing the congregation. Latimer did the same with her own daughter. Elders do the same for today’s youth, including Braylan. He and fellow YPD members conduct service and read scripture from the pulpit on the fourth Sunday of the month.

“They’re really polished, too,” member Janice Goodlow said..

An uplifting, each-one-teach-one ethos has been central to St. John’s mission since its humble start. After meeting in private homes for its first years, the congregation built a succession of North O worship spaces. Easter morning 1923 Rev. W.C. Williams, with associate ministers, the choir and congregants dedicated the current space, singing 'We're Marching to Zion.” Worship was held in the lower level. Nearly a quarter century later, Easter 1947, the congregation marched upstairs to commemorate the new sanctuary.

St. John’s grew prominent enough to host the 1948 AME regional conference.

Ties that Bind

Art, architecture and history students often visit the church to admire the clean lines and tiered construction, the large stained glass windows and the in-house museum, which offers glimpses of St. John’s and North O’s gilded heyday in photos, artifacts, even ashes from a mortgage burning. “Everything in here is a piece of our history,” said curator Janice Goodlow. “This is my heart.”

Surrounded by photos of past members, current St. John’s pastor Rev. Keith D. Cornelius said, “We’re standing on the shoulders of all these great people who established this church.”

Photo credit: St. John AME Facebook page

Two faithful mothers of the church, Goodlow and Latimer, both active in the Women’s Missionary Society, celebrated St. John’s 156th anniversary last fall. It was a small event compared to the 150th and 100th milestones, as the church’s ranks have dwindled. At its peak, Goodlow said, “It was packed. There was a lot going on.” In 1949 her family moved to Nebraska from Texas, where they were AME pastors, stewards, deacons. “We helped build the church,” she said of the denomination tracing its start to 1816, when Bishop Richard Allen formed AME in Philadelphia as a refuge from discriminatory white churches.

Goodlow recalled her first St. John’s pastor, Rev. Sanders Lewis, as “a very dynamic speaker.” After graduating from Omaha Central High School and then college, she drifted away from church. “I was raising a daughter and working full-time. Church was not relevant for me.”

Goodlow worked 43 years for Union Pacific Railroad, retiring as an instructional designer in its IT department. Upon her return to St. John’s, she felt a pull to stay that she hadn’t felt before. Charismatic pastor Clifton Neal St. James captivated her, but the church felt like an extension of her family. “The building just grabbed me, and I haven’t left since then. This feels like home now. This is the place I feel the most at peace, the most comfort. I’ve been to other churches and many felt cold. This is a warm church.” She said her brother Dennis Stewart is the “Jack of all trades at the church.” Her mother, a lifelong member, died in 2019.

“My friends at the church have always supported me during good times and bad. We had an excellent and heart-warming home-going service for my mom. This is a very supportive group, always willing to help and reach out.”

The warmth members often ascribe to St. John’s is something Cornelius has felt since arriving to pastor it in 2019. “The people are warm. The energy in the church – you have to be here to feel it and to witness the kind of love the brothers and sisters have.”

Typical with any new assignment, he said he made an initial “assessment” of St. John’s, careful not to make wholesale changes “because of the historical significance of the church and what it stood for and what it still stands for now.” Raised Baptist in St. Louis, where his great-grandmother was a storefront preacher, he followed his then-finance, now wife, Emma J. Campbell Cornelius, into the AME. She’s an educator. The couple have five adult children and seven grandchildren. “I just built on the healthy foundation already here, expanded the teaching, increased Bible study, launched a prayer line.” He also implemented leadership training sessions where members learn “what it means to lead, not just from the pulpit, in carrying out church” as stewards, deacons, committee heads, et cetera.

Members say Cornelius has increased the church’s community engagement. “There wasn’t a lot of life in the church. People weren’t doing things. We weren’t having a lot of different events,“ Goodlow said. “This man has us doing so much stuff now.” It helps, Mosely said, that he’s “a powerful pastor” whom members want to follow.

“The people are warm. The energy in the church – you have to be here to feel it and to witness the kind of love the brothers and sisters have.”

Cornelius said he knew of St. John’s reputation. “This is where African Americans met to discuss how they were going to proceed in meeting different challenges. It was a meeting place for activists.”

That activist-advocacy role particularly played out under the Rev. Edward Sneed Foust, who pastored the church during the entire decade of the 1960s, when the civil rights and Black Power movements led to legislative change.

Foust worked with the local NAACP and Citizens Coordinating Committee for Civil Liberties or 4CL in calling out injustice and demanding action. Several succeeding pastors, including Cornelius, have been active in the Omaha Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance as a platform for addressing issues.

Cornelius is also aware that St. John’s membership rolls once featured Black influencers. “It’s one of those silk stocking churches, meaning a whole lot of influential people have been members or come through this church at some point in time,” he said.

Omaha Star founder-publisher Mildred Brown, who used her newspaper and position to support civil rights efforts and to denounce racist practices.

Early Black state legislators John Adams Jr. and John Adams Sr., along with Edward Danner and George Althouse, were all members.

The Myers Funeral Home family belonged.

Educators have been well represented, going back to Welcome Bryant, Shirley Bryant, Evelyn Montgomery and late OPS assistant superintendent Don Benning. Current OPS Superintendent Cheryl Logan attends services. OPS Title I director Tina Forte, a third generation church member, directs St; John’s youth programs. “Tine Forte does a phenomenal job getting youth together, making sure they participate in our youth Sundays,” Cornelius said.

The church’s community outreach has meant some dramatic initiatives. In the ‘20s, it helped launch a neighborhood sewing factory employing Black women. In the ‘60s it developed a $2 million federally funded multi-unit affordable housing project at 34th and Lake under HUD’s Good Neighbor Homes program. The site housed some 120 low income families. St. John’s was among a number of churches nationwide providing affordable housing in the midst of urban renewal and redevelopment initiatives. The church eventually lost control of that complex, renamed Tommie Rose Garden and more recently Yale Park, to outside interests who were assailed for major code violations and unsafe conditions that forced residents to move out.

“Churches played significant roles in building affordable housing in the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s,” Cornelius said. “The problem was we didn’t know how to manage them. It takes dedicated staff to do that. The churches that do housing now either staff it internally or outsource its management.”

St. John’s operated a North 24th St. center to aid members and neighbors with employment leads, child care services, affordable housing options, and clothing. It also offered an after-school program. While it’s gotten out of the housing business, it helps people with utility payments, offers financial wellbeing workshops and convenes economic development forums.

“Our congregation is a lot smaller these days, but this is one busy group. ”

Cornelius said when he arrived at St. John’s he saw a need to “let folks know we’re still here, we’re still being active, we’re still being a part of the community.” Coinciding with his fresh mandate, he said the Women’s Missionary Society reassembled after a period of inactivity, “and they’ve been rolling ever since,” he said. “The support we get from church members is just phenomenal. That’s not always the case in churches. Sometimes you may come to a church and it’s almost like Ezekiel asking the Lord ‘Can these dead bones live again?’ You may have to go in and resurrect some stuff. But when you’ve got people like we have here that have a desire to work for the church and the community it’s a blessing.”

“Our congregation is a lot smaller these days,” Goodlow said, “but this is one busy group.”

The Women’s Missionary Society made about 30 harvest Baskets for Conestoga School (left) and the Jesuit Academy (right) for Thanksgiving in 2021. Both are title 1 schools with large concentrations of low income students.

St. John’s prepares holiday food baskets for needy families of children attending nearby Jesuit Middle School and Conestoga Elementary School. Some baskets go to families referred to the church and others go to parish families. A recent campaign collected bath and facial towels for residents of a local women’s shelter. Similar drives donated personal care items to Project Hope clients and infant care items to teenage moms served by the Child Saving Institute. St. John’s also does clothing drives. In conjunction with Clair Memorial United Methodist Church, it hosted a COVID-19 vaccine clinic.

A church-led community garden helps connect St. John’s with its neighbors.

Calls for social justice abound in this Black Lives Matter era and while Cornelius doesn’t use the pulpit to preach on systemic racism and specific acts of police misconduct or school-workplace bias, he does invite parishioners to address these concerns through such avenues as the Omaha Branch of the NAACP.

Get Me to the Church on Time

If St. John’s is to grow its small, aging-out flock with younger members, Goodlow believes, it must find ways to resonate with today’s families.

“I want church to become a place that is relevant for their lives,” she said, “but I’m not sure they’re interested in organizations like the church or the NAACP. I’d like to see us give them whatever is relevant to help their lives smooth out. I think we can do that through some different programs.”

Latimer is confident whoever needs to be there will come as long as St. John’s stays true to its core. It’s all about planting seeds of faith that sprout into the fruit of followers. “The church’s main function of introducing the Christian spirit and knowing the love of Christ never gets old, never dies. That’s always new in each of our lives.” she said. “We have to introduce the love of Christ and how to function in this world with Christ in our heart and love for one another. As long as we keep that the focal point, we will grow from there.”

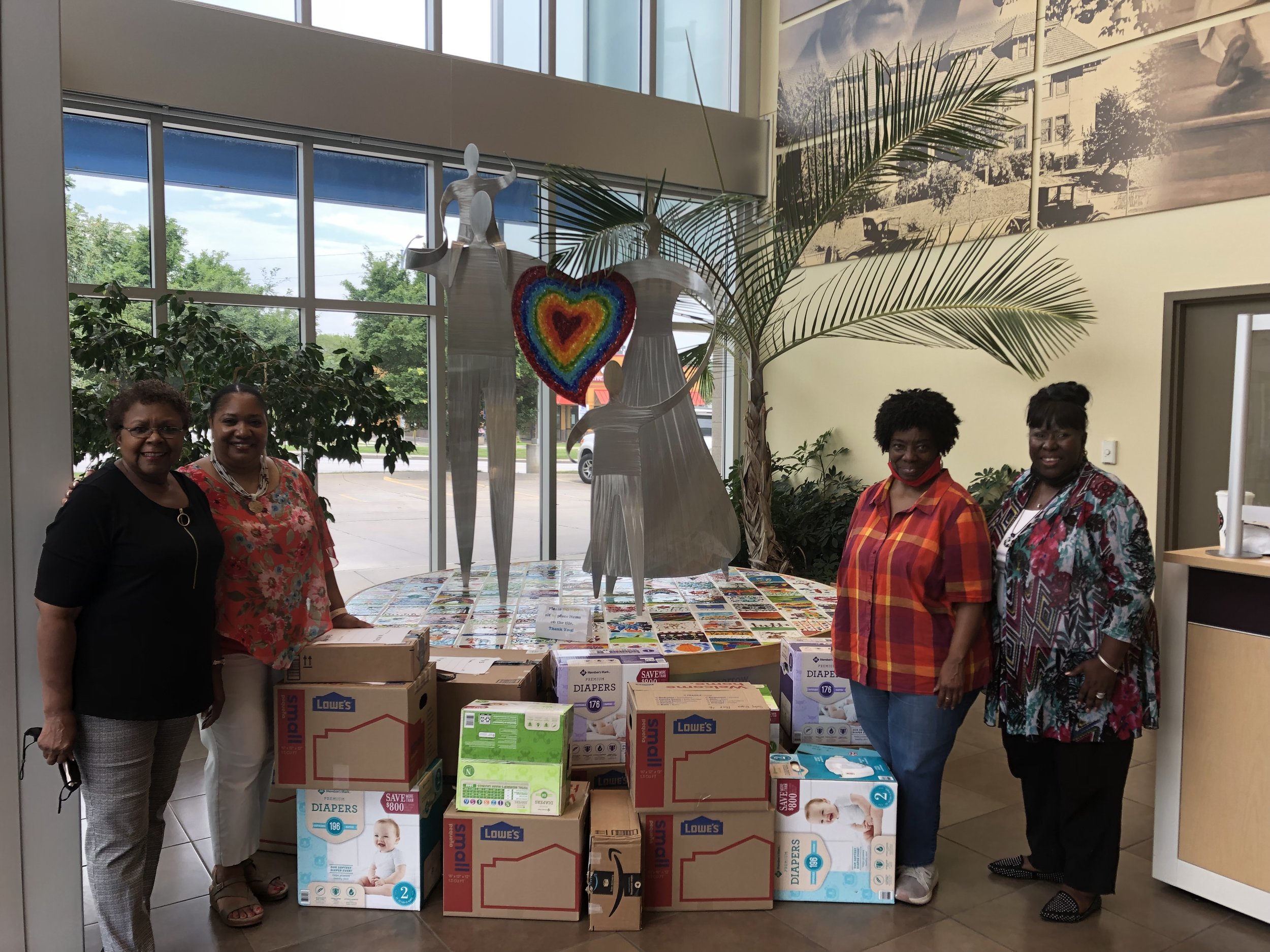

The Women’s missionary society donated baby items to the child saving institute (CSI) in 2021. from left to right, Alberta Nelson, Tina Forte, Louise Latimer and Evell Thomas.

Folks without blood relations nearby can use a church family, Latimer suggests. “If you don’t have that church connection, you’re just isolated. You may not have anybody thinking about calling or visiting to see how you’re doing. We do that with our church sisters and brothers. That’s the importance of the fellowship.”

When Latimer adopted her daughter, she said, “The church members embraced her as extended family.” Her church family was there again when her parents died.

Church during the pandemic has meant reduced attendance as people opt for online versus in-person participation.

“Pastors are battling that kind of mentality,” Cornelius said. “To pastor in this environment is difficult because it calls for creativity, innovation. It causes you to look outside these walls to see how you can put together programs that will enrich the lives of people. Technology is the thing now to focus on. We’ve evolved. We do church live on Facebook and Zoom. We do all that stuff.”

He’s well-versed in what traditional, mainline churches like his are up against.

Rev. Keith D. Cornelius

“We’re standing on the shoulders of all these great people who established this church.”

“Young and middle-aged people are tied to technology with phones, tablets, social media. They are now engaged in that world. They won’t come in the building. But we can go to them with technology. Evangelism is different. You have to fish differently now than you did 30 years ago. When I grew up you stayed in church all day long. You did morning Bible school and service, then you ate, and by the time you left church it was five, six, seven in the evening. You can’t do that now. An hour tops. Maybe an hour and a half on a first Sunday. After that, you lose people.”

Breaching the divide between old and new, he said, “is a work in progress” for the Black Church. “It’s a very difficult task because young people have a certain mindset about how church should be. We can’t traditionalize it because they’ll run away. Their songs are different, they’re more contemporary. Those in music ministry have learned how to combine the traditional with the contemporary to make it more upbeat, exciting. You have to do such things because if not young folks are going to find it elsewhere. It may not be a denomination like African Methodist, Baptist or Pentecostal. We have to sit down and talk with our youth about how we can serve them.”

It doesn’t help that the arch conservative Black Church is out of step with LGBTQ rights.

“It’s a challenge,” Cornelius concedes, “In order to survive the world we’re in we have to be able to address issues at the forefront. We’re slow, to say the least, but I think we’ll get there. I just don’t know how and when. There are old-line AMEers or believers with certain views. Others have more progressive, moderate views. The best thing that could happen is we come to some compromise on what it means to be inclusive.”

Open Hearts, Open Minds, Open Doors

Two daunting problems churches struggle with are fewer people attending church and older parishioners dying. But those challenges pale in comparison to earlier ones. St. John’s has shown resilience in surviving wars, riots, pandemics, depression, recession. Said Latimer, “It gives us a warm feeling knowing that a lot of churches, businesses, organizations don’t make it this long. Even though we’re small in number from what we used to be. I think the spirit is great. When we celebrate our anniversary each year we’re grateful.”

“We celebrate that we made it another year,” Goodlow said.

In keeping with its historic identity as a community standard-bearer, the church began hosting the annual Dream Keepers Awards in 2016 to celebrate Black excellence in Omaha. Past Dream Keepers honorees include Richard Webb, Terri Sanders, Preston Love Jr., Jerry and Ramona Bartee, Michael Carter, Jimmy and Gracie Smith, Kathy Tyree, and Don Benning.

The church has had to get creative at ways to bring the congregation together during the pandemic.

“One of the most successful and out-of-the-box events we had was our CDC Guidelines Tailgate Party in 2020 when COVID was still raging,” Goodlow said. “We grilled out in the parking lot, pre-packaged the food, did our masks, hand sanitizer and social distancing. We had some people come that hadn’t been at church in a while. They loved it because they could sit around their vehicles to do fellowship.”

Cornelius is open to ideas that bring people out, saying, “As we get back into fellowship and coming together those are things we have to do.

Even though we still have to be careful with COVID, the fellowshipping is what’s important because in fellowship you may be able to solve an issue that someone’s having. It’s where you can find solutions or resources or referrals for things going on. It’s an opportunity to get out and be with others so you won’t be so isolated. You really don’t know what’s going on with someone unless you sit down, talk and break bread with them.”

When Latimer considers the small congregation today, she’s sad so many faces are gone. “They were individuals I looked up to and had a history with. I miss them. It’s a challenge for us to grow. We’re now the ones remaining. Those that came before us kept it going. We’ve got to keep it going. We’re small in number, but there’s definite life, and I want to see it grow. Just us working together keeps us moving forward. That’s my inspiration.”

To Cornelius it’s almost sinful this tiny congregation has excess facilities – commercial kitchen, buffet service, fellowship hall, meeting-conference rooms – that rarely get utilized. “There’s a lot of space here,” He plans opening these resources to the community to serve as hub, incubator, shared office spaces for start-up businesses and things like tele-medicine conferencing. Making that a reality will require physical upgrades. He knows he can count on his congregation to do what they can, but he also knows funding must come from foundations and other granting organizations.

“We have to be open to a more diverse membership and devising ways to meet the needs of this cultural mix of younger families in our surrounding area”

“We have faithful givers. They tithe,” he said. “This is the older generation – the pillars of the church. They don’t mind giving to the church as long as the church is transparent in what we’re doing. I try to be as transparent as possible with how we handle the money that congregants give.”

St. John’s future may hinge on how successful it is in tapping the neighborhood’s new melting pot of white, Hispanic, African, Karen and African American residents. “We have to be open to a more diverse membership and devising ways to meet the needs of this cultural mix of younger families in our surrounding area,” Latimer said.

The church invites anyone to experience its aesthetic beauty, rich history and radical welcome. The hope, Cornelius said, is that folks who attend a dinner or rent space downstairs will sample a sanctuary service upstairs. In matters of the spirit, there’s no telling how a message of hope, love, mercy and forgiveness will land with someone. That’s how this church’s membership could grow again, he said, and add a new chapter to its next milestone.

“Once the pandemic truly clears up, I do see us coming back strong,” Shaunielle Mosley said. “We are about the people. We are always welcoming.”